Stories from Clay: Indigenous Art Pottery at the Tucson Museum of Art. Reflections with Collections Research Fellow Gabriella Moreno.

By Gabriella Moreno, Collections Fellow, Special Projects

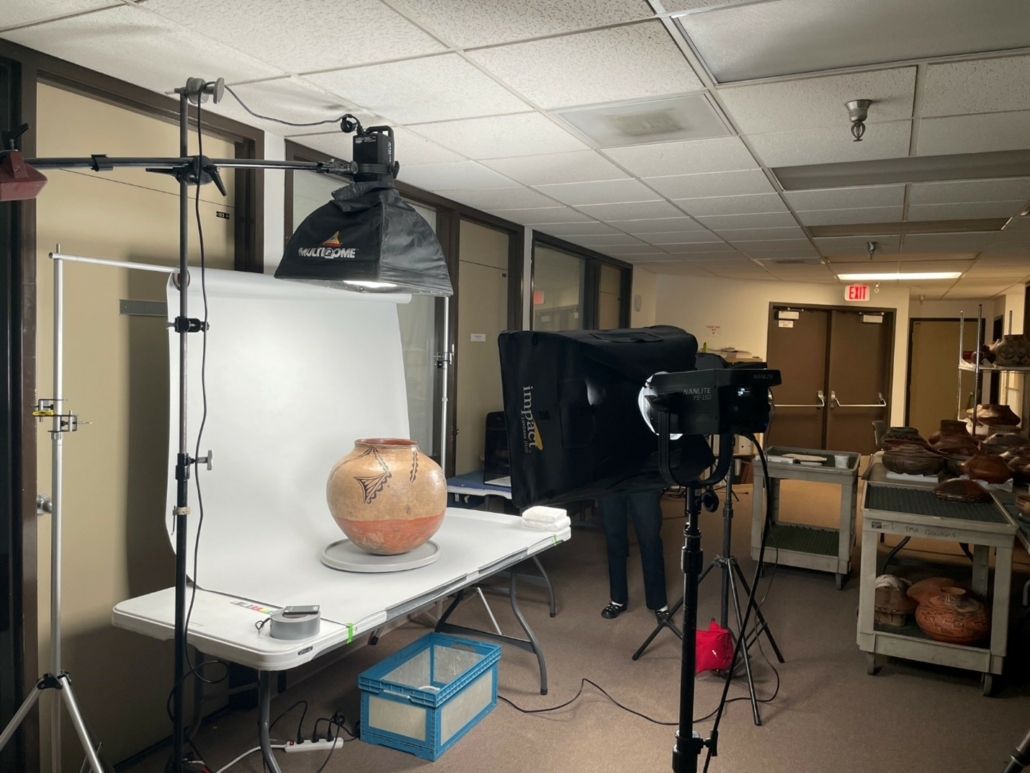

Ancestral Hopi, Homolovi, Utilitarian Jeddito Olla, 1100, painted earthenware. Collection of the Tucson Museum of Art. Museum Purchase. Virginia Johnson Fund. 1994.25

A few months ago, I joined the Tucson Museum of Art as the Collections Research Fellow. In this position, I will contribute to an ongoing effort to examine, catalog, and provide context to the museum’s permanent collection of historical Indigenous art pottery—84 ceramic vessels dating prior to 1900 with cultural and archaeological origins in what is now the Southwestern United States. In 2020, when the museum welcomed many of these items into its Indigenous Arts collection, curators committed themselves to their proper care and stewardship, a commitment now made possible through funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH).

A recently awarded grant from the NEH, entitled Stories from Clay, has allowed me to join a research, collection’s care, and community outreach team here at TMA dedicated to the extensive study and careful consideration of these vessels. The first stage of my research has focused on developing accurate collections records: learning more about these items, their cultures of origin, and the variety of historic ware types produced across the four-corners region and the Rio Grande River Valley. Although we hope, when possible, to provide details of attribution and identification, the greater purpose of this grant is to become better stewards of the collection. This will include developing relationships with Indigenous community consultants and participating in discussions that center culturally relevant approaches to collections care and research.

From January to April of this year, TMA began preparatory research, initiated community conversations, and developed relationships with organizations involved in the collection and study of this material. When I joined the team, we turned our attention to the vessels themselves and to the details of their materiality. Here’s a peek into what we did last month:

Collections Fellow, Gabriella Moreno, prepares a large Pueblo storage jar to be photographed. Due to the delicate nature of the pottery and to avoid potential slippage, the vessels were carefully handled with clean, gloveless hands.

In May, I worked with TMA’s Registrar and Collections Manager Rachel Adler and a photographer to produce 10 high-resolution images of each vessel. These stills may be studied individually or combined for a 360° view of physical details such as shape, wear, texture, and design scheme. The production of high-resolution images is a crucial step in the early stage of this project as it lays material ground for the collaborative spirit in which we hope to proceed. Despite the constraints of time and distance that define post-pandemic connectivity, we can now share these items via digital communication with Indigenous makers and scholars. Through a digitized community review process that privileges Indigenous knowledge, we hope to provide an intersectional platform for the study of this ceramic art form. This will be a process through which the voices of those holding cultural insight and experience come together to inform our understanding.

Ancestral Cochiti Pueblo storage jar (ca. 1845 AD) sits atop a handcrafted turntable.

By the end of our week-long photography session, it became clear to me that what the photographic medium fails to capture is the spirit of presence inherent in the clay itself. Consider, for example, the Ancestral Hopi water jar pictured above and its relation to the creation story of the Hopi people. As a mixture of earth and water, clay is not only an artistic medium, but also a sacred material that speaks to the emergence of the Hopi from the earth and from its clay. In conversation with community collaborators, we have learned that for centuries Hopi potters have kept this relation to clay close at hand when lending it form, and that a finished pot is thought to be an entity possessed of life and breath. This is all to say that the life of a pot transcends its captured image, and that the privilege of being in its presence is significant. In the coming months, we look forward to sharing this documentation with our Indigenous colleagues and to expanding the role of research to include clay’s material and spiritual presence. As I look forward, I wonder, how might clay teach us to hear the stories it tells?

Hours

Museum Hours:

Wednesday – Sunday,

10 am – 5 pm

Information

Newsletter

"*" indicates required fields