The Story of a Painting: José Gil de Castro’s Carlota Caspe y Rodríguez

By Dr. Kristopher Driggers, Assistant Curator, Schmidt Curator of Latin American Art

Since 1977, TMA has stewarded a portrait by an important Afro-Peruvian artist of the nineteenth century, José Gil de Castro. This week, the museum is opening an exhibition dedicated entirely to his portrait of young Carlota Caspe y Rodríguez. It is unusual for the museum to create an exhibition around a single work of art, but the story behind this painting is particularly complex and relevant to our moment. Created in Santiago in 1816, today we appreciate that the painting sits at the intersection of multiple narratives. On the one hand, it shows a young woman articulating her place in society. On the other hand, it also speaks to Gil de Castro’s intention to ascend in society by creating portraits for elite patrons. The painting on view at TMA lives at the intersection of their interests and distinct positions.

José Gil de Castro, Portrait of Señorita Doña Carlota Caspe y Rodríguez at the Age of Ten, 1816, oil on canvas. Gift of Frederick R. Pleasants, 1977.28.

Carlota Caspe y Rodríguez was ten years old when her portrait was made. She was the daughter of a Spanish administrator working in South America, though we know little else about her life. Looking at the image, we see her wearing a blue dress, necklace, and rings, and holding a bejeweled fan. Women in South America’s elite were often painted with similar imagery; for that reason, the painting connects Carlota with a broader social world of women of her time. Interestingly, she appears with a work of sheet music labeled moderato – a work meant to be played at moderate tempo and volume. Scholars have suggested that the label might apply not just to her music but to Carlota as well, as moderation was an important virtue for women of the early 19th century.

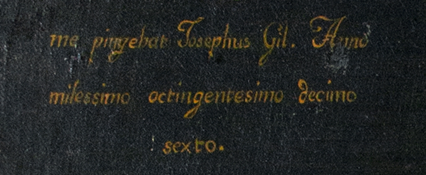

Detail of José Gil de Castro’s Signature

While the painting offers an image of Carlota, in many ways it is also a portrait of the artist who created it as well. Born to enslaved parents, the painter Gil de Castro (1785 – 1840) seems to have sought to disassociate his identity from his origins by modifying his signature on his paintings. We see his self-fashioning at work in the painting at TMA. Rather than signing the painting in Spanish, Gil de Castro writes in Latin:

Me pingebat Josephus Gil Anno milessimo octingentesimo decimo sexto.

I was painted by Josephus Gil in the year One Thousand Eight Hundred Sixteen.

Gil de Castro’s decision to sign in Latin was surely intentional since Latin had long been the language of science and theology. In this signature, he even changed his name from José to Josephus, Latin-izing his self-presentation to style himself as a learned artist. In the long run, his strategy appears to have been successful, as Gil de Castro would come to paint many of the most important figures in newly independent Latin American nations from Chile to Venezuela.

In Latin America today, many institutions and private collections hold Gil de Castro’s portraits. However, TMA’s painting may be the only painting by the artist in a U.S. museum. It was donated to TMA by Frederick Pleasants, a founding contributor to the collection, who is believed to have purchased the work while in Europe.

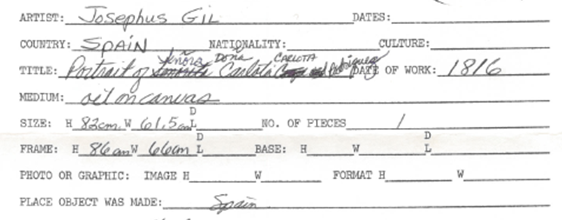

Detail from the painting’s accession form created in 1977

As part of this exhibition, curatorial staff reviewed the original documents from when the painting was donated to the museum. These revealed an unexpected history: Early on, TMA staff believed the painting was created by a Spanish artist, and files state that the painting was created in Spain. Though this error was likely due to a lack of accurate information, it also led to the erasure of Gil de Castro’s identity as an Afro-Peruvian artist. Records were updated in 2013 when the museum was contacted by researchers in Perú working on a major exhibition of Gil de Castro’s work. Their work shows us the importance of undertaking research to effectively steward monuments of Afro-Latinx cultural production at museums today.

Photographs of Carlota’s portrait under blacklight

In addition to archival work, TMA staff also looked closely at the physical condition of the painting. Under blacklight, we see that while most of the painted surface is likely original, there are also areas where inpainting was added, probably to cover up areas of loss. The canvas was apparently folded before coming to the museum, as a fold line appears in the painting’s lower half. Staff examined the painting outside of its frame and noted that it had been relined – meaning that its canvas was attached to a second canvas to give the old painting more support.

Many works of art in the TMA collection weave together multiple stories. In the case of Carlota’s portrait, those stories concern the aspirations of an Afro-Peruvian artist, the social negotiations of a young woman, the itinerary of a work of art as it entered the museum, and the preservation and alteration of artistic materials over time. Gil de Castro’s painting reminds us of the complex life of an artwork and reminds us to consider how other artworks might have been shaped by distinctive interests and narratives.

Hours

Museum Hours:

Wednesday – Sunday,

10 am – 5 pm