Art and Chocolate: A Halloween Highlight with José Guadalupe Posada

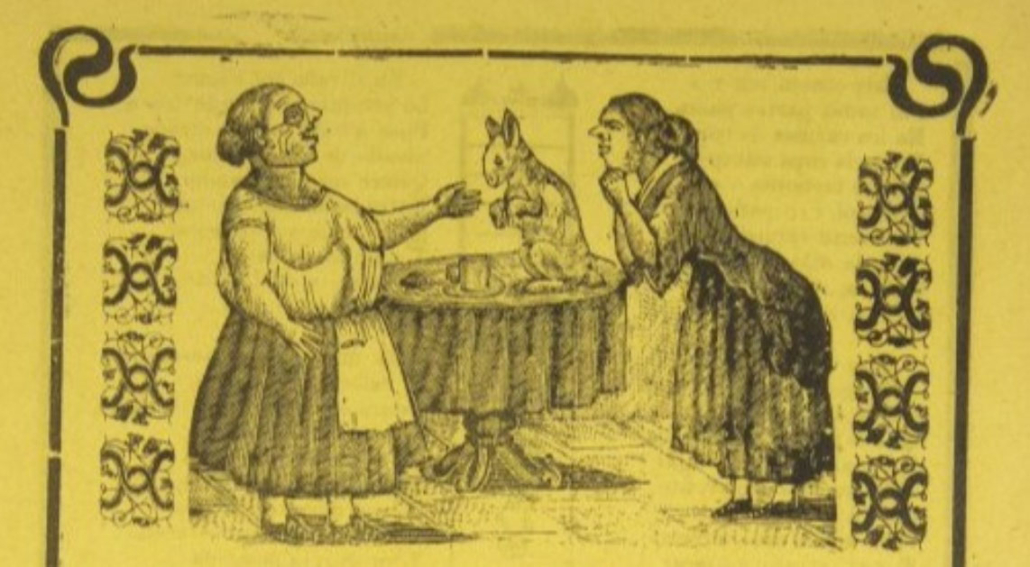

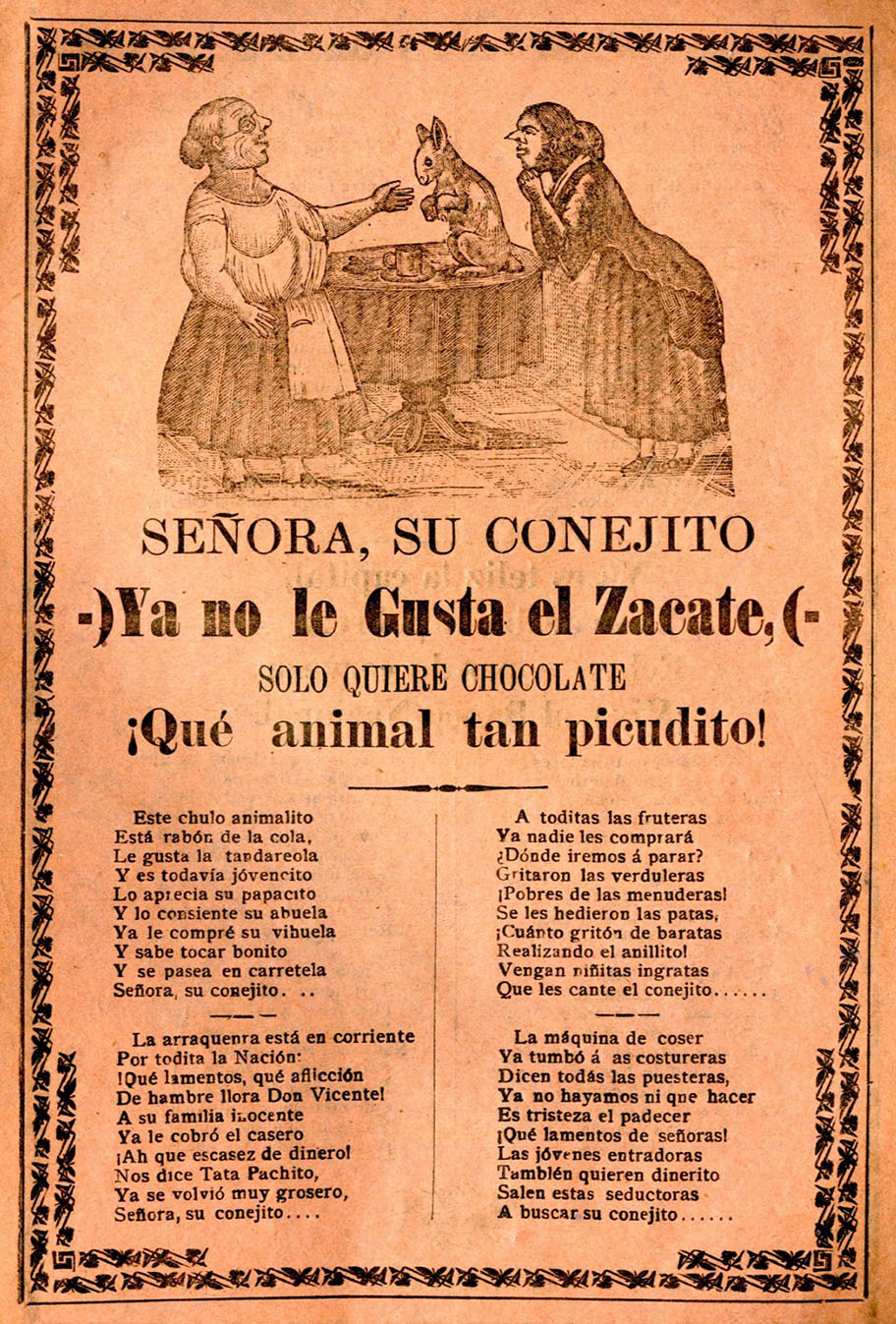

Jose Guadelupe Posada, Señora, Su Conejito… (Madam, Your Little Rabbit…), (detail), ca. 1900-1920, lead engraving on yellow newsprint, 11.75 x 7.75 in. Gift of Posada Art Foundation on behalf of A. James Nikas Jr. 2020.38.2

On Halloween there’s a good chance your thoughts turn to chocolate. According to Forbes.com, Reese’s Cups are America’s #1 Halloween candy. M&M’s, Hershey Kisses, Snickers—those all rank in the top 10 as well.

Yes, chocolate tastes good, but there are so many more reasons for art lovers to think about it. Like many other foods, chocolate has been both medium and subject for artists. While food in general is ubiquitous, the regional, cultural, economic and aesthetic factors that influence specific food choices and depictions make it a rich metaphor for so much more than meeting physical needs.

(By the way, if you’re in Tucson before March 20, 2022, visit our friends at the University of Arizona Museum of Art to see The Art of Food, an exhibition of more than 100 works by prominent 20th and 21st century artists that considers food beyond its purpose as body fuel.)

Consider the newest chocolate in TMA’s permanent collection: it’s found in a recent acquisition—a broadside created around 1904 containing a poem or corrido and an image by the Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada. Broadsides were one of the most common forms of printed material between the 16th and 19th centuries. Printed on the cheapest paper available and plastered onto walls as a form of street literature, they usually contained announcements, advertisements or social commentary in the form of ballads.

Below an image of two women discussing a rabbit who happily eyes a cup of drinking chocolate, Señora, Su Conejito… (Madam, Your Little Rabbit…) declares “Señora, su conejito ya no le gusta el zacate, solo quiere chocolate. Que animal tan picudito!” (“Madam, your little rabbit doesn’t like to eat grass anymore—he only wants chocolate. What a clever little animal!”).

Following the illustration and headline is a corrido—a narrative poem that could be sung as a ballad. Both music and language are simple in a corrido, generally with eight or fewer syllables in each line, making them easy to remember and pass along orally. The songs are often about oppression, history and other socially relevant topics. Until the arrival of electronic mass-media in the mid-20th century, the corrido was the main informational and educational outlet in Mexico.

Despite the visual depiction of two matronly women and a rabbit, the poem on this broadside is actually about the perceived excesses of actors in the political realm at the time the work was created. The chocolate-eating rabbit, referenced in the last line of each verse, is a metaphor for the senseless consumption and luxury of the upper class.

Broadsides were often printed more than once. This example contains the same image and text as the work in TMA’s collection, but the different color of paper and the variation in the page border indicate that it was created in a different print run.

About the Artist: José Guadalupe Posada

José Guadalupe Posada Aguilar was born in Aguascalientes, Mexico, in 1852. One of eight children, he learned reading, writing and drawing from his older brother Cirilo, a country school teacher, before joining the Municipal Drawing Academy of Aguascalientes. As a teenager he apprenticed in the workshop of Jose Trinidad Pedroza, who taught him lithography and engraving. He began his career as the political cartoonist for a local newspaper, El Jicote (The Bumblebee), where his first cartoons were published. He relocated to Mexico City in 1888, where he established a workshop. He died in 1913 during the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920).

Academics have estimated that during his long career, Posada produced more than 20,000 images for broadsides, pamphlets and chapbooks. According to Benedict Heywood, who curated an exhibition of Posada’s work in 2018 at Bellevue Arts Museum in Washington, the single-page penny prints weren’t designed to be kept. The fact that many of the originals were saved is a testament to the strength of Posada’s imagery. His work has influenced numerous Latin American artists and cartoonists because of its satirical acuteness and social engagement. Post-revolution muralists also drew inspiration from his work.

Hours

Museum Hours:

Wednesday – Sunday,

10 am – 5 pm